The CAGED system is a super helpful tool to understand and navigate the fretboard.

It helps you make sense of chord shapes, scale shapes, riffs, melodies, arpeggios…

Anything that happens on the fretboard.

This is awesome, because understanding the fretboard can give you greater freedom to play what you want to play, and express yourself on guitar.

Now, I know the CAGED system can seem a little confusing and complex, but it really doesn’t have to be.

I see a lot of well-meaning explanations of CAGED that throw complicated and overwhelming fretboard diagrams at you, which only make sense if you already understand how the fretboard works.

So, in this article, I’ve broken down CAGED into 6 easy-to-understand insights about how the fretboard works.

Each of these insights is useful and valuable in itself. So even if you stop at insight 3 or 4, you’ll already have learned a lot!

We’ll start with some quick questions about CAGED: what is it, how should you learn it, and is it worth learning?

Let’s check it out!

Introduction

What is the CAGED system (and should you learn it)?

CAGED takes all the fretboard shapes you’ve already learned, from chords to scales and riffs and melodies, and shows you how they’re connected.

It collects all those puzzle pieces you’ve learned so far and puts a frame around them.

This solidifies what you already know and makes it easier to add new things to your understanding of the fretboard, like LEGO blocks.

In other words, CAGED is a summary of how the fretboard works that someone decided to give a name to.

As I’ll show you in this article, it’s made up of some very common-sense insights that will help you make sense of the fretboard.

How to learn CAGED?

This also brings us to an important point about learning CAGED.

Please, don’t try to memorise expansive CAGED fretboard charts.

The value of CAGED is in understanding the underlying logic, not in studying endless fretboard shapes.

The CAGED logic allows you to learn a new scale or chord shape, and easily add it to what you already know.

That way, you’ll slowly expand your understanding of the fretboard, bit by bit.

So my goal with this article is this. Instead of memorising fretboard shapes, I want you to understand why the CAGED system works as it does.

Is CAGED worth learning?

Perhaps I should start this answer with a confession: I never learned CAGED.

It wasn’t until I’d been playing for close to a decade that I found out that CAGED was ‘a thing’.

But when I looked into it, I thought: “yes, that’s how the fretboard works, that’s how I think about it as well.”

This is actually the experience of many guitar players. They learn how the fretboard works and only later find out that this is, apparently, a ‘system’.

In reality, CAGED is just a way of describing the logic of the fretboard. The ‘system’ is already there on the fretboard.

In short, whether you decide to explore CAGED or not, you’ll end up learning what CAGED teaches anyway.

Step 1

Why is this ‘system’ called CAGED?

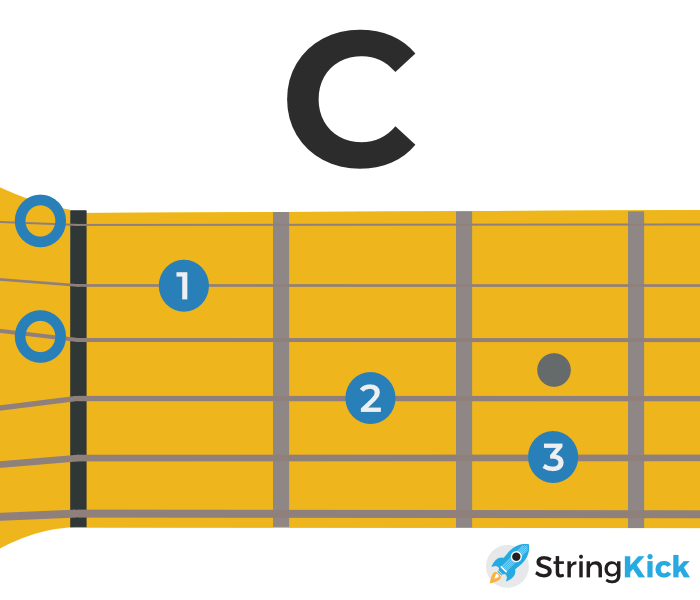

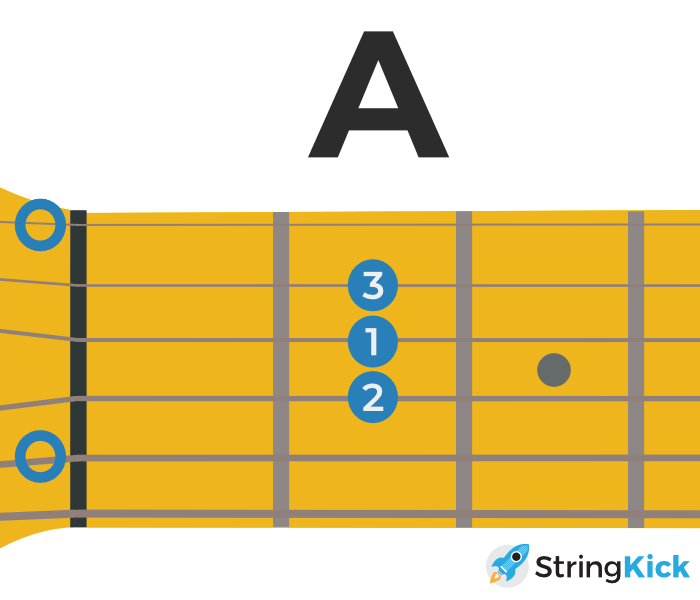

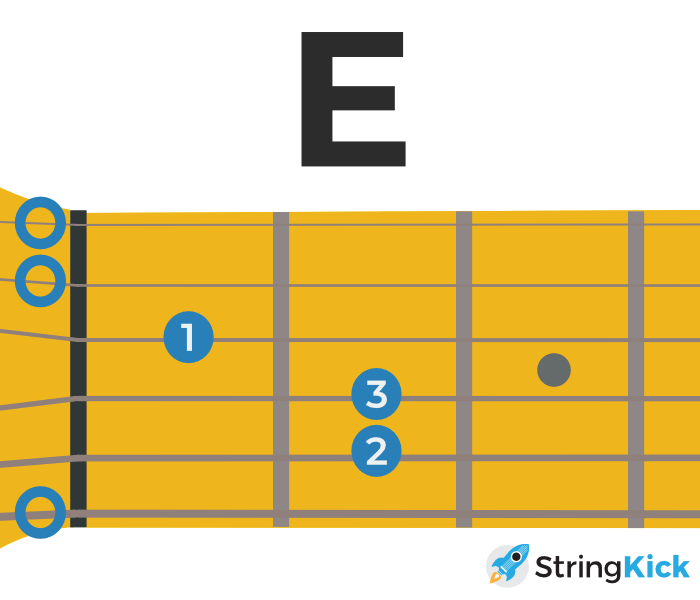

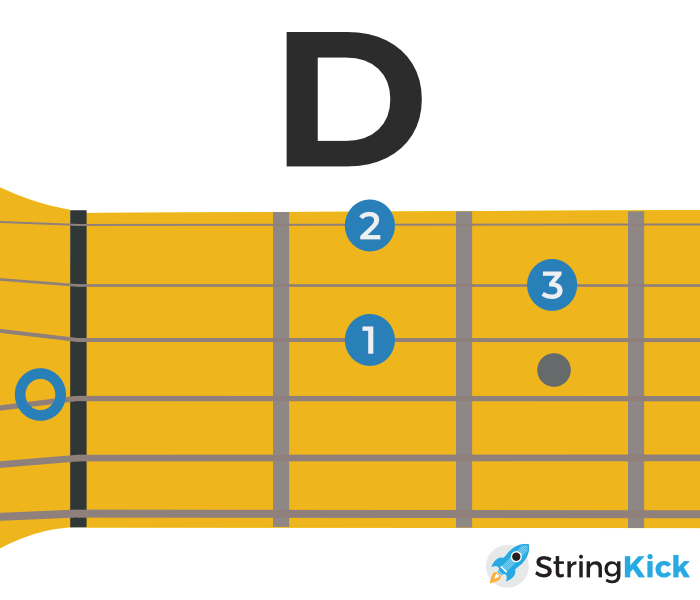

The name of the CAGED system refers to the 5 open major chords: C, A, G, E and D.

We’ll use the fretboard shape of these chords to understand and navigate the rest of the fretboard.

So, if you’re not yet comfortable with your open chords (both major and minor), I recommend you focus on learning a bunch of songs first, before you start learning more about the CAGED system. It simply won’t make as much sense without that prior knowledge.

Step 2

The Shapes are moveable

Say we have an open A chord.

If we move every single note in this chord up one fret, we’ll create a different chord: Bb.

The only difference is that A is an open chord (meaning it has open strings), while Bb is a barre chord (because we’re barring our index finger). The difference between an open chord and a barre chord is only a matter of guitar technique by the way. In terms of music theory, it’s the exact same.

We can keep moving around this chord shape. For example, when we play it in 3rd position (i.e. with our index finger in the 3rd fret), we get a C chord:

And when we play it in 7th position, we get an E chord:

As you can see with all the chords, the chord shape remains the exact same. Simply by moving the shape around the fretboard, we can create different chords. In fact, this is why barre chords are so useful to learn.

This particular shape is called the ‘A shape’, because it is based on the open A chord. The name can be a little confusing, because as we saw, we can use the ‘A shape’ to play C chords and E chords. In fact, we can play any chord with the ‘A shape’. So the name is just a reference to a shape on the fretboard.

Step 3

We can make changes to the shapes to get new things

We’ve only seen major chords so far, but we can change them into different chord types such as minor chords, minor seventh chords, dominant chords and so on.

Let’s check out an example.

Here’s a D chord, based on the A shape again.

Now, we can change this into a D minor chord (Dm) by changing a single note. All we need to do is lower the B string by one fret.

We can also turn it into a D major seventh chord (Dmaj7), by lowering the G string one fret.

Or we can turn it into a D7 chord, by lowering the A string two frets.

Now, you’re probably wondering: how do I know what strings I need to change?

This is where music theory comes in. We need to know what intervals are, how to play them on guitar and how chords are constructed.

Before we explore this further though, if you’re completely new to changing chord shapes, please don’t worry about the theory behind it yet. Instead, focus on memorising these chord shapes without yet understanding them. Learn the ‘E shape’ barre chords and the ‘A shape’ barre chords, in all sorts of variations. You can have a lot of fun with just 3 or 4 of these barre chord shapes and play lots of songs with them. To find out more about this, check out Guitar Chord Bootcamp: Barre and Beyond.

Now, let’s run through the theory quickly. I won’t go into too much detail in this article on this, but you can read more about it in my article on music theory for guitar.

For this explanation, I’m assuming you already have an understanding of intervals on guitar.

In short: every ‘chord type’ (major, minor, major seventh etc.) has certain ‘chord ingredients’. For example:

- Major chord: R, M3, P5

- Minor chord: R, m3, P5

- Major Seventh chord: R, M3, P5, M7

R = Root

m3 = minor third

M3 = major third

P5 = perfect fifth

M7 = major seventh

To be able to change chord shapes, we need to know not just what the chord shape looks like, but which ‘chord ingredient’ every note is.

For example, here is the D chord again, with the ‘chord ingredients’ indicated:

As you can see, it has the three ingredients that a major chord should have: a root note (R), major third (M3) and a perfect fifth (P5).

The ‘recipe’ for minor chords is slightly different. Instead of a major third (M3) we have a minor third (m3). So, here’s the D minor(Dm) chord with its ‘chord ingredients’:

In short, we can change the shapes by knowing the ‘recipes’ for the chord type we want to create. If we then know where each ‘ingredient’ is located, we can change what we need to change.

If you’re an All Access member, you can get more practice with this in Music Theory from Scratch. It has exercises where you can practice these chord shapes, analysing every single ingredient.

Not a member yet? You can still get started and try the first couple of lessons for free!

Step 4

Chord shapes are the foundation for scale shapes

For example, how we can turn an A chord into an A minor (Am) chord, or even an A minor seventh (Am7).

But we’re not stopping there. The next big insight is that the chord shapes are actually the foundation for scale shapes too.

Let me show you what I mean.

Here’s a D minor chord (Dm), played in the 5th position.

Now, the cool thing is that we can add a couple of notes to this chord shape to get a D minor scale shape. Check it out:

As you can see, we added a couple of new ingredients: M2, P4 and m7. This completes our ‘recipe’ for the natural minor scale:

- Root (Or 'Tonic')

- Major Second

- Minor Third

- Perfect Fourth

- Perfect Fifth

- Minor Sixth

- Minor Seventh

What’s great about this insight, is that your knowledge of chords on the fretboard, supports your knowledge of scales and scale shapes.

It works the other way round too: you can use your knowledge of scales to understand chord shapes, and perhaps to find new, exciting chords on the fretboard.

Overall, making this connection strengthens your knowledge of the fretboard and makes everything easier to remember.

Now, you don’t need to go and memorise a bunch of scale shapes right now.

The most important takeaway here is that chord shapes and scale shapes ‘overlap’ on the fretboard. They are, in terms of fretboard logic, sort of the same thing. Everything is connected.

Step 5

The CAGED open chords have a hidden structure

But there’s actually a hidden, but simple structure to them. We can divide the shapes into two categories:

1. Left

2. Right

Now, what do I mean by this?

Every chord starts with the root note. That’s the lowest note in the chord, and the letter we use to name the chord.

For example, with the G and E shapes, the root note is on the low E string. But from that root note, these chord shapes go in a different ‘direction’. The G shape goes ‘left’ and the E shape goes ‘right’

We also have two shapes with the root note on the A string: the A and C shape. One goes left, the other goes right:

Finally, we have the D shape, with the root note on the D string. This shape goes ‘right’:

You might be wondering, don’t we have a chord shape with the root note on the D string, that goes ‘left’? And we do! It’s the "F shape":

However, we tend to leave this out of the CAGED system, because the F shape, is actually the top part of the E shape:

In short, we have shapes with root notes on the E, A and D string. From that root note, we can go ‘left’ or ‘right’ to get different shapes.

Step 6

The C, A, G, E and D shapes are connected

For example, here are the A and C shapes again:

And here’s E and G:

But those aren’t the only shapes that connect: they’re all connected!

In fact, when you lay them out on the fretboard, they spell out C-A-G-E-D. Check it out:

Now, don’t worry about memorising all of this in one go.

Again, the goal is to realise that all these shapes are connected to each other.

The most useful place to start is to know the ‘neighbors’ of the shape you’re most comfortable in.

For many players, that will be the E shape. So it’ll be helpful to know how to transition into the D shape or G shape.

This is the power of the CAGED system. It structures all those little bits and pieces you know about the fretboard and connects them. This makes it easier to move around, playing different chords and playing melodies in different places on the neck.

Conclusion

Next Steps

So, where do you go from here? How do you use the CAGED system to improve your understanding of the fretboard?

It's actually quite simple: one tiny thing at a time. Whether it’s a new chord shape or a heavy guitar riff. You can make sense of it using the CAGED system and connect it to what you already know.

So the answer is to take real songs and analyse them. See how they’re constructed and how they fit into the bigger picture!

As always, if you have any thoughts or questions, feel free to message me here.

![Title image for Learn Music Theory for Guitar [5-step Roadmap]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Music-Theory-for-Guitar-Main.png)

![Title image for The Major Scale on Guitar [Simple Explainer]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Major-Scale-Guitar.png)

![Title image for Guitar Intervals: Explained Easily [Full Guide]](https://www.stringkick.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Guitar-Intervals-Title-Image.png)